The Kish Project, 2004-2006

The Status Quo

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP1-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP1-large.jpg]

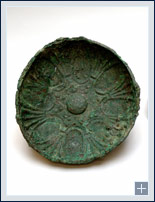

The elaborately painted vessel from which these sherds came was decorated with various insects and animals that abounded in the area at the time. They include scorpions, fish, birds, and a gazelle nursing her young.

Jamdat Nasr. Baked clay. Jamdat Nasr Period. Field Museum 158345

For the eight decades since their excavation, the collections from Kish have remained divided, with forces of fate, scholarly predilection, geography, and international politics precluding the production of a synthetic site report for the city. Accounts of The Field Museum-Oxford University Joint Expedition to Kish were originally published in the 1920s and 1930s by both Langdon (1924, 1930, 1934), who wrote a popularly oriented series, and Mackay (1925-1929 and 1931), who was responsible for a series of more scientific publications. However, Watelin died in 1934 and Langdon in 1937, with the result that no final site report was ever produced.

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP2-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP2-large.jpg]

This elaborate dagger, made of exotic and costly materials, was useful only to demonstrate the wealth of its owner. Because the iron was cast long before the techniques of heating and forging were developed, it would have been too soft to be used, and the ivory handle would have fragmented upon any type of impact.

Kish. Iron, ivory, gold. Early Dynastic Period. Field Museum 236415

McGuire Gibson (1972) and Roger Moorey (1978) both revisited the products of the excavation in the 1970s, and since these seminal publications, the archaeological assemblage from Kish frequently has been the subject of scholarly inquiry. Works have been produced on the private houses and chariot burials at Ingharra (Algaze 1983-84), on cuneiform texts from the city (Dalley and Yoffee 1991), on the physical character of its inhabitants (Rathbun 1975), and, most recently, on the nearby site of Jamdat Nasr (Englund and Grégoire 1991, Matthews 2002). Forthcoming works on the previously excavated Kish collection focus on the cylinder seals (Gibson, in preparation), and additional cuneiform tablets (Dalley, in press). However, a synthetic site report resulting from the 1920s and 1930s excavation is still lacking. As Kish may have been one of the first true cities of the world, and one of the first places to hold any sort of regional power, the lack of a final site report stands as a significant gap in the archaeological record of Mesopotamia.

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP3-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP3-large.jpg]

Expedition Staff. From Left to Right: Ernest Mackay, Field Director; Stephen Langdon, Director; and Col. W. H. Land, Topographist

1923-24 Season. Oxford Negative 213

In late 2003 the US federal government, through the auspices of the National Endowment for the Humanities, developed a special Iraq initiative offering substantial funding to projects to preserve and document Iraqi cultural resources. This program offered the unique opportunity for funding of efforts dealing not only with collections within Iraq, but also with those materials of Iraqi cultural patrimony exported to Europe and America. The appropriateness of this funding opportunity was not lost on The Field Museum, which sought, and received, the funding necessary to revisit, after nearly a century, the collections from Kish. This initial funding for the Kish Project has been substantially augmented by both private donations and, in late 2005, by an appropriation from the United States Congress which will make possible the ambitious project goals outlined below.

Challenges

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP5-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP5-large.jpg]

This bowl is decorated with interlaced lotuses, which are probably of Egyptian inspiration.

Tell Barguthiat. Copper alloy. Neo-Assyrian/Neo-Babylonian Period. Ashmolean Museum 1933.1355

As with any effort to resurrect the work of old excavations, the Kish Project has been presented with a large number of challenges, some resulting from the style and execution of the excavation and others from decades of neglect of the excavated materials.

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP4-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP4-large.jpg]

The chariots/carts found in the Y Sounding at Kish are the earliest wheeled vehicles known. They and the other contents of these rich burials attest to the wealth and power of the individuals interred there. A photograph of the wheels as they appear today can be seen in the Object Gallery.

Kish East, Ingharra, Y Sounding, Chariot Burial 2. 1927-28 Season. Negative 59675

Principal among the former challenges is the dispersal of the excavated objects to the four corners of the globe. This division, and the poor documentation that accompanied it, has certainly resulted in the irreversible loss of context and association for a sizeable number of artifacts. In addition, problems with the original recording methods have often proven difficult to overcome. For example, neither Mackay nor Watelin established a long-term, systematically conceived program of operations or a logical, ongoing system of recording. In fact, both excavators changed their registry methods in mid-stream, using alphanumeric designators that at times referred to provenience designations, at others to patron names, and finally to a general sequence of finds. In addition, for at least two seasons, duplicate field numbers were assigned. Moreover, a combination of the poor quality of excavation and the subsequent division of the artifacts has resulted in an utter lack of consistency in the way in which the collected artifacts are described. Object types, materials, even loci, are referred to in an idiosyncratic and inconsistent manner, with the result that a new standardized cataloguing terminology has had to be developed and applied to all available objects. These factors, combined with the generally slipshod style of excavation, the lack of any consistent onsite director, and the death of both Watelin and Langdon within five years of the close of excavation have all combined to create a rather desperate situation.

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP6-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP6-large.jpg]

Like many expeditions in the 1920s and 1930s, the Kish Expedition moved great quantities of earth, often using railway cars of a type employed in mines. The cars were moved by groups of men or boys, rather than by machinery. Some of those cars and the tracks on which they ran are visible in this photograph.

Kish East, Ingharra. 1927-28 Season. Negative 66754

Subsequent treatment of collections at the three holding institutions also has not lived up to the standards of today. For example, when The Field Museum assigned registration numbers to Kish objects as they entered the collection, field numbers were often removed, presumably with an eye toward aesthetics. Thus objects were dissociated from their field records. Some of these associations can be recovered by methods such as use of a black light to read erased numbers; others will have to take place with the aid of drawings and photographs, where such exist. Even in instances where numbers were not intentionally removed, deterioration such as soluble salt efflorescence or bronze disease have resulted in the physical disassociation of many objects from their field numbers. Finally, in the 1920s and 30s, archaeologists could not have seen the importance of the unglamorous remains (e.g., sherds, bones, lithics) that today constitute a vast realm of archaeological possibility. Thus at least 10,000 of these pedestrian artifacts were never even given registration numbers in the field or at their respective holding institutions, but languished in obscurity.

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP7-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP7-large.jpg]

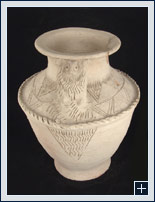

During the Isin-Larsa/Old Babylonian period, small clay plaques of the type shown here were extremely common. They bear representations of deities and cultic or mythological scenes, and may have been objects of private devotion or amulets that served to ward off evil and/or attract beneficial forces.

Kish. Baked clay. Isin-Larsa/Old Babylonian Period. Field Museum 156861

As briefly mentioned above, issues of politics have also conspired to make more difficult a full reconciliation of the scattered Kish collections. Issues of safety and security have prevented a full appraisal of the state and condition of the Kish collections held by The Iraq Museum (which should have the largest and "best" collection of the three holding institutions). Until the storage room doors at the Iraq Museum are re-opened, any attempted reconciliation of the results of The Field Museum-Oxford University Expedition will necessarily be incomplete. The groundwork for the incorporation of the Iraqi portions of the Kish materials has and is, however, being laid with the training of Iraq Museum staff by Kish Project personnel and the establishment, for the first time since 1928, of lines of communication between Field Museum, Ashmolean Museum, and Iraq Museum administrators. The general lack of security in Iraq today has also affected directly the site of Kish, both preventing further site revisits or excavation and increasing the pace of looting therein. Project staff are, however, in contact with US Military personnel stationed at the site and have been assured of the security of at least some portions of its mounds.

Project Goals and Methods

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP8-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP8-large.jpg]

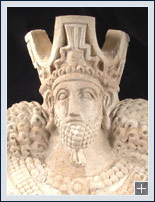

The Kish Expedition excavated seven buildings whose walls were embellished with elaborate stucco decoration. The figure shown here is that of a Sasanian king, identified by his crown as either Shapur II (A.D. 310-379) or Bahram V (A.D. 420-438).

Kish East, Mound H, Sasanian Palace 1. Stucco. Sasanian Period. Field Museum 236400a

The ultimate goal of the Kish Project is the production of a site report which will draw together the fruits of ten seasons of excavation into a unified, synthetic, and comprehensive statement on the culture and history of ancient Kish. It is only through the production of such a report that a detailed reckoning of the city's illustrious place in history can be had. Given the nature and distribution of the excavated materials, however, a number of necessary antecedent steps were required. Principal among these was the production of a catalogue of the Kish holdings of the Ashmolean Museum and The Field Museum of Natural History, which reconciles, for the first time since excavation, these scattered collections of material culture from Kish. This document, which has both print and digital incarnations, includes a reckoning of not just all of the excavated objects, but also of the trove of documents produced by the excavators during the ten seasons of excavation. The catalogue is not intended to be a simple list of materials, but rather aims to be the first earnest attempt to reconstruct object assemblages by provenience.

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP9-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP9-large.jpg]

Jars with handles in the form of a crude human figure, with prominent breasts and a large pubic triangle, were common in graves of the Early Dynastic III period at Kish. They are called "goddess-handled jars," but the identity of the figure(s) they represent and their purpose within the graves remains a mystery.

Kish East, Mound A, West Side of Mound. Baked clay. Early Dynastic Period. Field Museum 156212

In order to produce this catalogue, Field Museum staff members have traveled to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford to inventory extant archival records and to photograph over 2,000 Kish objects prior to their being packed in anticipation of a major construction project. The Ashmolean generously offered to loan all its Kish archival materials to The Field Museum for the duration of this project. This 16 cubic feet of documents included everything from original Expedition field cards, notes, correspondence, and photographs to the entire corpus of Kish documentation compiled over a period of three decades by longtime Kish scholar Roger Moorey. All of the collections-related records from The Field Museum and Ashmolean Museum Kish collections were entered on computer (some 20,000 object records), and all the photographs produced by the expedition, numbering over 5,000 images, were scanned.

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP10-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP10-large.jpg]

Stone bowls were found in many of the burials at Kish. The fact that the stone had to be imported as well as the considerable number of man-hours needed to work it into a finished form suggest that only the wealthiest individuals would have been able to afford such vessels.

Kish East, Ingharra, Y Sounding, Burial Y521. Stone. Early Dynastic Period. Field Museum 156462

In addition, each Kish object at The Field Museum was photographed digitally (over 9,000 images) and was examined in order to establish a standard cataloguing terminology for the new object database. An electronic object catalogue, following this standardized terminology and including photographs, was produced for The Field Museum and Ashmolean Museum collections. At the moment, circumstances in Iraq prevent our working there—former President of the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage in Iraq, Donny George, has told us that all the storerooms have been welded shut to prevent further looting. However, we believe that eventually we will be able to establish, at the minimum, a basic catalogue using the detailed notebooks preserved in the papers of Roger Moorey, who spent an extensive period of time in Baghdad in the early 1970s studying Kish material there. Staff working on the Kish project have identified and scanned relevant archival material such as the weekly reports sent back from the field by both Mackay and Watelin and original plans and drawings—all of which are being used to reconstruct the archaeology of Kish to be presented in the final site report.

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP11-large.jpg]

[/kish/fieldmus/images/KP11-large.jpg]

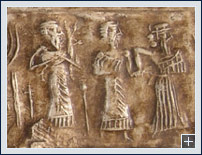

Seals were invented in the Near East approximately 10,000 years ago and are still used in Iraq today. Ancient Mesopotamians used seals to seal doors and containers in which items were traded or stored. An intact sealing indicted that no one had tampered with the contents and identified the agent or agency that had affixed the seal. After writing was invented, seals were impressed on documents, sometimes by administrative officials, at other times by witnesses to legal transactions, to validate the written records.

Kish. Shell. Akkadian Period. Field Museum 156670

The dissemination of the catalogue of the three Kish collections that will have been completed by the end of the present project will be accomplished through both traditional print and digital media. The printed edition of the Kish catalogue will be bilingual (English/Arabic) and will include introductory chapters by the appropriate curator(s) and eminent scholar(s) in the field of Mesopotamian archaeology, an explanation of the process and methods used in its production, and a richly illustrated detailing of the materials held by each institution. In addition, the results of the Kish catalogue are being disseminated by means of this web site, which contains text in both English and Arabic. This database links together in a dynamic manner object descriptions, object photos, digitized versions of related field records, and relevant field photographs, allowing the user the ability to literally click-down to the level of individual trenches, graves, etc. in order to "see" the site of Kish and the collections as they were when excavated, in effect to reverse the process of their division.

The Field Museum

The Field Museum, 'The Kish Project, 2004-2006', The Field Museum's Kish Database Project, 2004-09, The Field Museum, 2025 [http://oracc.org/kish/fieldmus/KishPast,PresentandFuture/KishProject,2004-2006/]