Ezida (temple of Nabû at Borsippa)

Ezida, the temple of the god Nabû and the main religious structure in Borsippa, is not only well attested from numerous cuneiform sources, but also from its substantive archaeological remains. The temple, which was originally dedicated to the god Marduk (in his manifestation as Tutu), was the fifth most important religious structure in Babylonia, at least according to a first-millennium-BC hierarchical list of temples. It is listed twice in the so-called "Canonical Temple List": once as the sixth temple of Marduk (Babylon's patron deity) and once as the principal temple of Nabû (Borsippa's tutelary god). Construction work on Ezida is attested from the Old Babylonian Period (ca. 1900–1600 BC) to the Seleucid Period (323–63 BC).

Names and Spellings

Borsippa's principal temple went by the Sumerian ceremonial name Ezida, which means "True House"; that name is also attested for other temples of the god Nabû, including that deity's temples in the Assyrian capital city Kalhu (biblical Calah; modern Nimrud) and Nineveh (modern Kuyunjik and Nebi Yunus).

- Written Forms: e₂-zi-da; e₂-zi₃-da; e₂-zid-da.

Known Builders

BM 090865, a marble stele depicting Ashurbanipal carrying a basket on his head and recording that Assyrian king's restoration of the enclosure wall of Ezida. Image adapted from the Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, "Stela of Ashurbanipal," World History Encyclopedia. Photo Credit: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin.

- Old Babylonian (ca. 1900–1600 BC)

- Hammu-rāpi (r. 1792–1750 BC)

- Middle Babylonian (ca. 1600–1000 BC)

- Marduk-apla-iddina I (r. 1171–1159 BC)

- Marduk-šāpik-zēri (r. 1081–1069 BC)

- Nabû-šuma-imbi, governor of Borsippa; reign of Nabû-šuma-iškun (r. 760–748 BC)

- Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC)

- Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC)

- Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631 BC)

- Šamaš-šuma-ukīn (r. 667–648 BC)

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

- Neriglissar (r. 559–556 BC)

- Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC)

- Hellenistic (323–63 BC)

- Antiochus I Soter (r. 281–261 BC)

Building History

Hammu-rāpi, the sixth king of the First Dynasty of Babylon (ca. 1894–1595 BC), is the earliest-attested builder of Ezida, which at the time was dedicated to the god Marduk (in his manifestation as the god Tutu). That Old Babylonian ruler states that he (re)built Ezida, Marduk's "holy dais," without giving details about the project; this is typical of Akkadian inscriptions written at that time. After a significant gap in its building history, further details about the royal sponsorship of Borsippa's principal temple resumes with the Kassite ruler Marduk-apla-iddina I and Marduk-šāpik-zēri, the seventh king of the Second Dynasty of Isin (ca. 1157–1026 BC). Both kings state that they rebuilt Ezida. The former mentions that he worked on it on Marduk's behalf, while the latter states that he renovated the temple for Nabû (in his manifestation as Mudugasâ) after it had become old and dilapidated.

During the reign of Nabû-šuma-iškun, a Chaldean ruler of the Bīt-Dakkuri tribe who declared himself king of Babylon, the governor of Borsippa Nabû-šuma-imbi claims to have restored a storehouse of the Ezida temple, despite the fact there was turmoil in Borsippa and in Babylonia that disrupted religious traditions, including the statue of Nabû travelling to Babylon for the New Year's festival. The damaged Akkadian text recording this deed does not mention that Nabû-šuma-imbi undertook any work on the temple itself.

Ezida received a great deal of attention from the Assyrian king Esarhaddon and his two sons, Ashurbanipal (the king of Assyria) and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn (the king of Babylon). Esarhaddon decorated the temple's interior, principally by installing various metal(-plated) protective figures — wild bulls (Akkadian rīmu) and goat-fish (Akkadian suhurmāšu) — in its principal gateways and by plating a dais of Nabû, which was called the "Dais of Destinies" (Akkadian parak šīmāti), with a silver alloy covering; he also dedicated a bronze(-plated) chariot. Sometime between 668 BC and 652 BC, Ashurbanipal, who was then king of Assyria, continued the work of his father and set up four additional silver(-plated and inscribed) statues of wild bulls. These were placed in two prominent gateways: in the Gate of the Rising Sun and the Gate of Lamma-RA.BI. During that same period of time, Ashurbanipal, together with his older brother Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, who was then king of Babylon, had the enclosure wall rebuilt since it was reported to have become old and dilapidated. Both rulers set up steles inside Ezida to commemorate their deeds. Sometime after the death of Šamaš-šuma-ukīn in 648 BC, which effectively ended a long rebellion against Assyria (652–648 BC), Ashurbanipal stationed an additional pair of wild bulls in the Luguduene Gate, as well as outfitted the temple's interior with lavish appurtenances and architectural features; he set up silver(-plated) pirkus (meaning uncertain for this Akkadian word) in the gates Kamah and Kanamtila; and he fashioned a reddish gold threshold.

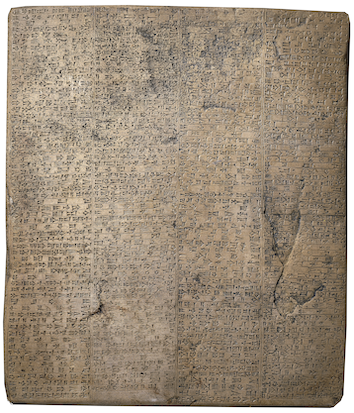

BM 129397, a large stone tablet that bears a long Akkadian inscription that is now commonly referred to as the "East India House Inscription." The description of Nebuchadnezzar's renovation of Ezida is recorded in lines iii 36–66. Image adapted from the British Museum Collection website. Credit: Trustees of the British Museum.

As with the temples at Babylon, most of the information that survives today about Borsippa's temples comes from the Neo-Babylonian Period (625–539 BC). Numerous Akkadian inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II attest to that ruler's rebuilding of Ezida. The longest presently-known description is found in an Akkadian inscription written on a large stone tablet. The relevant passage of the so-called "East India House Inscription" reads:

Nebuchadnezzar is also known to have given special attention to Nabû's cella (Emahtila) and one of the temple's principal gateways (Kaumuša), both of which he claims to have roofed and lavishly decorated. Moreover, he adorned a seat of Nabû (the "Dais of Destinies"), which was used during New Year's festivals (Akkadian akītu), with a new metal plating. According to inscriptions on bricks and paving stones, Nebuchadnezzar had a protective, subterranean base (Akkadian kisû) constructed around Ezida using baked bricks (Akkadian agurru) and bitumen (Akkadian kupru) and paved the Processional Way with baked bricks inside the temple (from the Kamah Gate to the Kaumuša Gate) and with breccia slabs outside the temple.

Nerglissar — an influential and wealthy landowner who married one of Nebuchadnezzar II's daughters (possibly Kaššaya) and later became king — like Esarhaddon and Nebuchadnezzar II, claims to have plated the "Dais of Destinies" with metal.

Borsippa also received some attention from Nabonidus, Babylon's last native king who occasionally referred to himself as "the one who renovates Esagil and Ezida" (Akkadian muddiš esagil u ezida). Although few extant texts of this Neo-Babylonian king record his work on Borsippa's principal temple, Nabonidus, like Ashurbanipal and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, focused his attention on the enclosure walls. He also planned to renovate the Processional Way, but unfortunately no details about that building enterprise survive today, apart from the king's intent to carry out the work. Parts of the interior were renovated. Following in the footsteps of his predecessors, Nabonidus had metal(-plated) statues of wild bulls set up in prominent gateway(s) of Ezida.

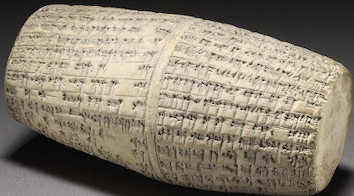

The last-attested builder of Ezida from presently-extant cuneiform sources is the Seleucid ruler Antiochus I Soter. This ruler's work on the Nabû temple is recorded in an Akkadian inscription written on a two-column clay cylinder. The relevant passage of that text reads:

BM 036277, a two-column clay cylinder bearing an Akkadian inscription of Antiochus I. Image adapted from the British Museum Collection website. Credit: Trustees of the British Museum.

Archaeological Remains

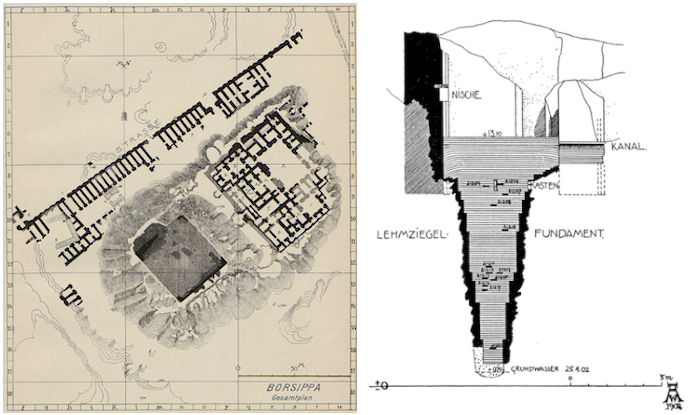

Borsippa has been excavated several times since 1854. Ezida's substantive remains were investigated by Hormuzd Rassam (1879–82), Robert Koldewey (1901–02), and Helga Piesl-Trenkwalder and Wilfred Allinger-Csollich (from 1980 onwards). This important building measured ca. 100×100 m, with approximately fifty rooms centered around five courtyards (labelled A–E). Nabû's cella (Room A₃), the building's holiest room, was located west of the principal courtyard (Court A), which was accessed from the temple's principal entrance (Gate G). Because the lower portions of many of Ezida's brick walls survive, most of the temple's plan is still recognizable today. In a deep trench excavated by Koldewey in 1902, the brick substructure, at least under the main cella (Room A₃), stretched down at least 13 m, to the level of the groundwater (in April 1902); several inscribed bricks of Nebuchadnezzar II were discovered in situ in that excavation trench.

Left image: Robert Koldewey's plan of the ruins of Ezida and Eurmeiminanki at Borsippa. Right image: excavation trench showing the foundation of the pedestal of Ezida. Images from R. Koldewey, Die Tempel von Babylon und Borsippa, p. 54 fig. 94 and pl. XI.

Further Reading

- Allinger-Csollich, W. 1998. "Birs Nimrud II: Tieftempel-Hochtempel: Vergleichende Studien Borsippa - Babylon," Baghdader Mitteilungen 29, pp. 95–330.

- Anonymous, "Borsippa," Wikipedia (English), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borsippa.

- Dandamayev, M.A. 2009. "Ezida Temple and the Cult of Nabu in Babilonia of the First Millennium," Vestnik drevnej istorii 3, pp. 87–94.

- George, A.R. 1993. House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations 5), Winona Lake, pp. 159–160 no. 1236.

- Koldewey, R. 1911. Die Tempel von Babylon und Borsippa (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 15), Leipzig, pp. 50–59.

- Rawlinson, H.C. 1861. "On the Birs Nimrud, or the Great Temple of Borsippa," The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 18, pp. 1–34.

- Reade, J.E. 1986. "Rassam's Excavations at Borsippa and Kutha, 1879–82," Iraq 48, pp. 105–116.

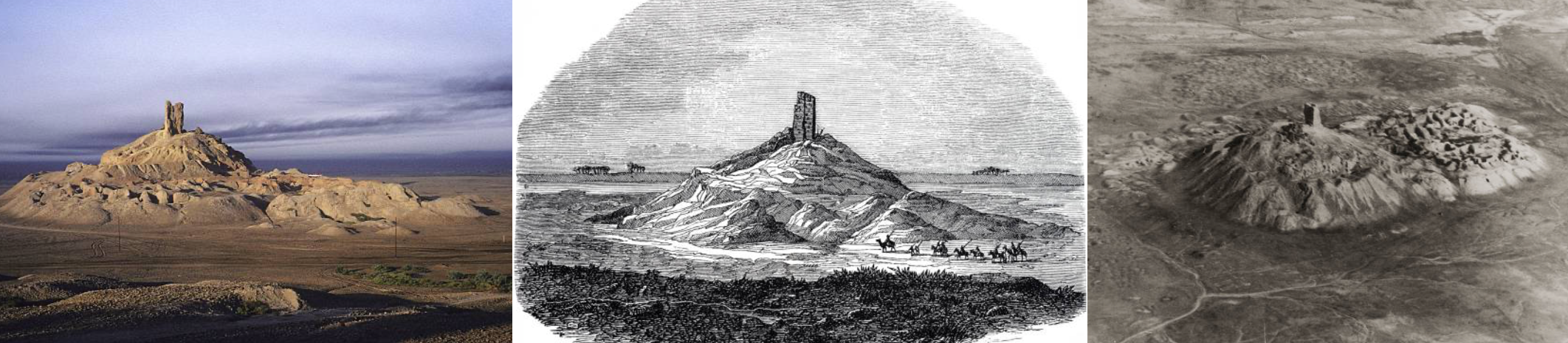

Banner image: photograph of the remains of Ezida and Eurmeiminanki taken ca. 2002 (left); woodcut from "Pleasant Hours: A Monthly Journal of Home Reading and Sunday Teaching; Volume III" published by the Church of England's National Society's Depository, London, in 1863 (center); areal photograph of the ruins of Ezida and Eurmeiminanki taken in 1928 (right). Images from Getty Images.

Jamie Novotny

Jamie Novotny, 'Ezida (temple of Nabû at Borsippa)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Borsippa/TemplesandZiggurat/Ezida/]