Eniggidrukalamasuma (temple of Nabû of the harû at Babylon)

According to Tablet IV of the scholarly compendium Tintir = Babylon, Eniggidrukalammasuma, the temple of the god Nabû of the harû, was one of the four temples located in the Ka-dingirra district of East Babylon and, according to that same text, it was one of the three religious buildings dedicated to Nabû at Babylon; the other two are Egišlaʾanki (in the Esagil complex in Eridu) and Ešiddukišarra (in the Tuba district of West Babylon). This small 1,080-m² religious building (Temple D I), which was built between the ziggurat Etemenanki and the South Palace, west of the Processional Way, was excavated and partly reconstructed in 1979–81 by Iraqi archaeologists led by Danial Ishaq. The ruins of the building were identified as Eniggidrukalammasuma from inscriptions discovered within its structure, including a clay cylinder of the later Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC), and from the colophons of tablets discovered in the northwest corner of the building.

Names and Spellings

This temple at Babylon went by the Sumerian ceremonial name Eniggidrukalamasuma, which means "House Which Bestows the Scepter of the Land." This name of the Nabû of the harû is attested in Babylonian Chronicles, colophons of school texts (found in Temple D I), lists of temples (including the Canonical Temple List, where it is mentioned as the third of Nabû's six temples), and royal inscriptions (from the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Periods). The name Eniggidrukalamasuma is also given to the Nabû of the harû built by the late Neo-Assyrian king Sîn-šarra-iškun (r. 626–612 BC) at Ashur (modern Qalat Sherqat), the principal religious center of Assyria.

- Written Forms: e₂-gidru-kalam-ma-sum-ma; e₂-nig₂-gidru-kalam-ma-an-sum; e₂-nig₂-gidru-kalam-ma-sum-ma; e₂-GIŠ.nig₂-gidru-kalam-ma-sum-ma; e₂-GIŠ.nig₂-gidru-kalam-ma-sum-mu.

Known Builders

- Neo-Assyrian (ca. 911–612 BC)

- Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC)

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

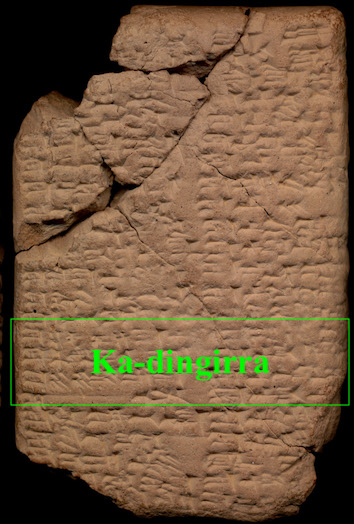

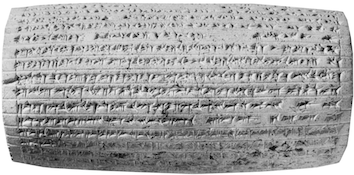

IM 142109, a single-column clay cylinder found deposited in the structure of Eniggidrukalamasuma that is inscribed with an Akkadian inscription of the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 BC). Image reproduced from N. Al-Mutawalli, "A New Foundation Cylinder from the Temple of Nabû ša Ḫarê," Iraq 61 (1999), p. 194.

Building History

Like many of the temples in Babylon, relatively little is known about the building history Eniggidrukalamasuma before the seventh century BC. Although the temple is mentioned in the so-called "Religious Chronicle" in connection with the Babylonian king Simbar-šipak (r. 1025–1008 BC), the founder of the Second Dynasty of the Sealand, killing a panther in its vicinity, the first, secure contemporary reference to it dates to the reign of the seventh-century-BC Assyrian king Esarhaddon, who, according to an inscription deposited in the structure of that temple, had Eniggidrukalamasuma rebuilt precisely on its original foundations. The relevant passage of that text describes the work as follows:

This work took place between 672 BC and 669 BC. Given the fact that Esarhaddon died before completing many of his building projects at Babylon, it is unknown if work on Eniggidrukalamasuma was finished before his death in 669 BC or if that project was completed by one of his two sons, the king of Assyria Ashurbanipal (r. 668–ca. 631 BC) or the king of Babylon Šamaš-šuma-ukīn (r. 667–648 BC).

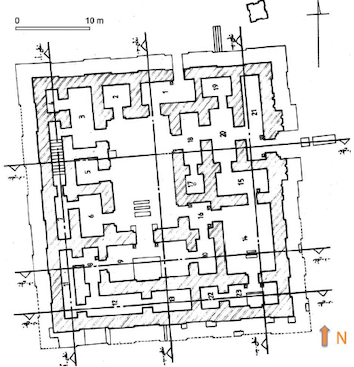

Plan of the Nabû of the harû temple at Babylon. Image from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 168 fig. 4.20.

While the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II was transforming Babylon into an imperial megacity, he completely rebuilt the unbaked superstructure of Eniggidrukalamasuma with "bitumen and baked brick." No further details about that project are presently preserved in the extant corpus of royal inscriptions of that Neo-Babylonian king.

Although the temple was in use at least until 78 BC (according to an Astronomical Diary, which states that fighting took place in its vicinity), nothing about its rebuilding is known after the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II. The Persian king Cambyses II, while he was still Cyrus II's crown prince, is reported to have entered Eniggidrukalamasuma during the New Year's festival held at Babylon in 538 BC.

Archaeological Remains

The substantial remains of Eniggidrukalammasuma were excavated and partly reconstructed Iraqi archaeologists in 1979–81; that team was led by Danial Ishaq. The ruins of this building, which are located in the area of Babylon known today as Sahn, were identified as belonging to the Nabû of the harû temple from inscribed clay cylinders deposited in its structure and the colophons of school tablets found in two of its rooms. This confirms the information provided in Tintir = Babylon Tablet IV, which stated that Eniggidrukalammasuma was located in the Ka-dingirra district of East Babylon. The reconstructed building that can be presently be seen in Babylon incorporates parts of the temples constructed by Esarhaddon and Nebuchadnezzar II.

Photograph of the decorated walls of the courtyard of Eniggidrukalamasuma taken in November 2018. Photo credit: Frauke Weiershäuser.

This small temple measured 35×37.5 m (1,080 m²) and had twenty-two rooms centered around two courtyards. The most important rooms, the cellas of Nabû and his consort Tašmetu (Rooms 9 and 23) were located south of the courtyards; the former room was the largest chamber in the building and it measured 14.8×8.7 m (130 m²). The walls were only 1.8 m thick; they are estimated to have been 9 m tall. In the reign of Esarhaddon, the walls were constructed of unbaked mudbrick (Akkadian libittu) and, in the time of Nebuchadnezzar II, they were made from baked brick (Akkadian agurru), just as those kings' inscriptions recorded. The walls were decorated with white lime-gypsum wall plaster and black bitumen, just like other temples at Babylon. The temple's base, at least in the Neo-Babylonian Period, was surrounded and supported by a baked-brick kisû. Lastly, two plastered, unbaked mudbrick altars were unearthed in front of the main entrance, which was located in the eastern façade.

In the northwest corner of Eniggidrukalammasuma, more than 1,500 clay tablets were unearthed. These are school tablets written by scribes in training.

Further Reading

- Cavigneaux, A. 1981. "Le temple de Nabû ša harê. Rapport préliminaire sur les textes cunéiformes," Sumer 37, pp. 118–126.

- Cavigneaux, A. 1981. Textes scolaires du temple de Nabû ša harê, vol. 1, Baghdad.

- Cavigneaux, A. 1985. "Nabû ša ḫarê temple and cuneiform texts," Sumer 41, pp. 27–29.

- Cavigneaux, A. 2013. "Les fouilles irakiennes de Babylone et le temple de Nabû ša ḫarê: Souvenirs d'un archéologue débutant," in B. André-Salvini, (ed.), La tour de Babylone: Études et recherches sur les monuments de Babylone. Actes du colloque du 19 avril 2008 au Musée du Louvre, Paris, Rome, pp. 65–76.

- George, A.R. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts, (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 40), Leuven, pp. 310–312.

- George, A.R. 1993. House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Mesopotamian Civilizations 5), Winona Lake, pp. 132–133 no. 878.

- Ishaq, D. 1985. "The excavations at the southern part of the procession street and the Nabû ša ḫarê temple," Sumer 41, pp. 30–33 [English section] and pp. 48–54 and figs. 1–18 [Arabic section].

- Pedersén, O. 2021. Babylon: The Great City, Münster, pp. 167–174.

Banner image: annotated satellite image of the Ka-dingirra district of East Babylon, including Eniggidrukalamasuma (left); photograph of the reconstructed Nabû of the harû temple taken in October 2015 (middle); digital reconstruction of Eniggidrukalamasuma (right). Image created by Jamie Novotny from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 169 fig. 4.22 and p. 172 fig. 4.26.

Jamie Novotny & Joshua Meynell

Jamie Novotny & Joshua Meynell, 'Eniggidrukalamasuma (temple of Nabû of the harû at Babylon)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/TemplesandZiggurat/Eniggidrukalamasuma/]