Summer Palace (royal palace in Babylon)

The remains of the so-called "Summer Palace," the third certainly-attested Neo-Babylonian royal residence in ancient Babylon, were excavated in Tell Babil, the highest ruin mound of the modern site, where local tradition has preserved Babylon's name until today. The long-reigning king Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC) constructed this new building inside the northernmost stretch of the newly-built outer city wall, about 2.5 km north of the "South Palace." This grand palace was constructed atop of a 22-m-high brick terrace and covered an area of ca. 26,000 m2. The Summer Palace, on account of its strategic location, served as a fortress, as well as a royal residence. The ruins of this once-grand palace was visited by Pietro della Valle in 1616 and excavated by Robert Koldewey on behalf of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (DOG) and Königliche Museen Berlin (KMB) in 1914–15, as well as by Iraqi archaeologists around 1980.

Names and Spellings

"Summer Palace" (German Sommerpalast) is the modern designation given to the building by the German archeologists who excavated its remains at the beginning of the twentieth century. This designation originated from the presence of niches in some rooms, which thought to have been ventilation shafts for cooling, and from its climatically favorable location at Babylon. This royal residence is also known as "Palace of Babil," its name according to local tradition. According to an Akkadian inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II, its founder, the palace was simply referred to as ēkallu, the Akkadian word for "palace," as well as by its Akkadian ceremonial name nabiʾum-kudurrī-uṣur libluṭ lulabbir zānin esagil, which means "May Nebuchadnezzar (II) Stay in Good Health (and) Grow Old as the Provider of Esagil."

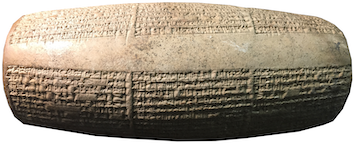

BM 091142, a three-column clay cylinder with an Akkadian inscription of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II recording his construction of the so-called "Summer Palace" at Babylon. Photo credit: Jamie Novotny.

- Written Forms: É.GAL; dna-bi-um-ku-du-ur₂-ri-u₂-ṣu-ur₂ li-ib-lu-uṭ lu-la-ab-bi-ir za-ni-in e₂-sag-il₂.

Known Builders

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

Building History

At the northernmost point of the newly-expanded city of Babylon, where the circuit of the new outer city wall of Babylon met the branch of the Euphrates River that ran through the city, the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II, the son and immediate successor of Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC), built himself a third palace. An Akkadian inscription written on clay cylinders commemorates this project. The relevant passage of that text reads:

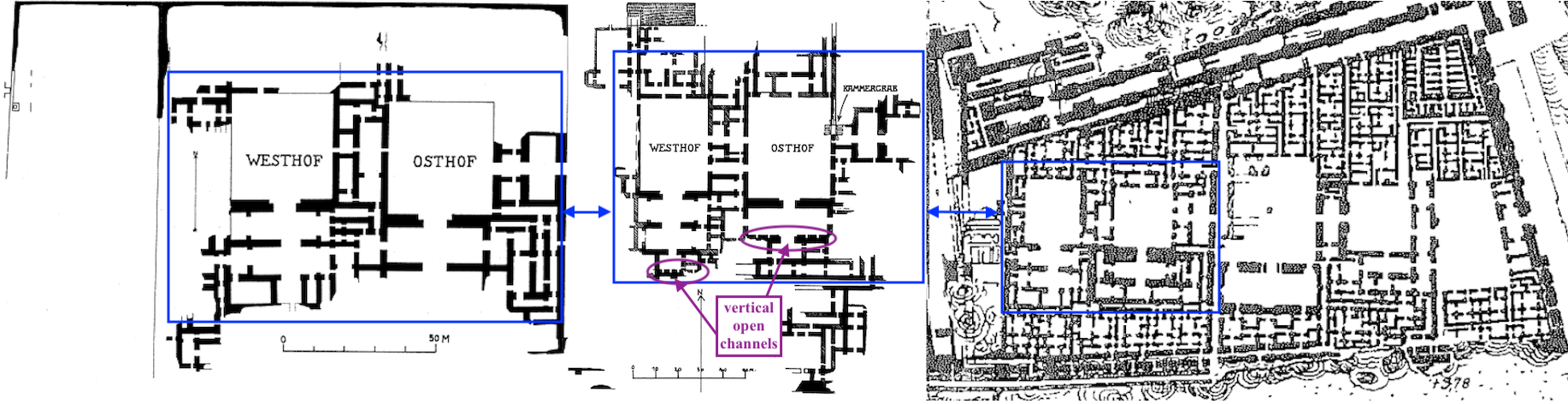

It is clear from its plan that the Summer Palace, which Nebuchadnezzar states that he constructed as a fortress to protect Babylon and its principal temple Esagil, was modelled on the newly-constructed North Palace, as well as the western extension of the South Palace (which was located in the Ka-dingirra district, in the northwestern corner of East Babylon).

Given the lack of sources, it is not known if any of Nebuchadnezzar's successors worked on this royal residence.

Despite the lack of textual evidence, it is clear from the archaeological record that the Summer Palace continued to be used during the Persian and Hellenistic Periods. At some point during the Parthian Period, this once-grand royal residence fell into disuse. Sometime during the late Parthian Period or in the Sassanian Period, a 180×180 m fortress was constructed on top of the Summer Palace's ruins, thus continuing its function as a defensive outpost.

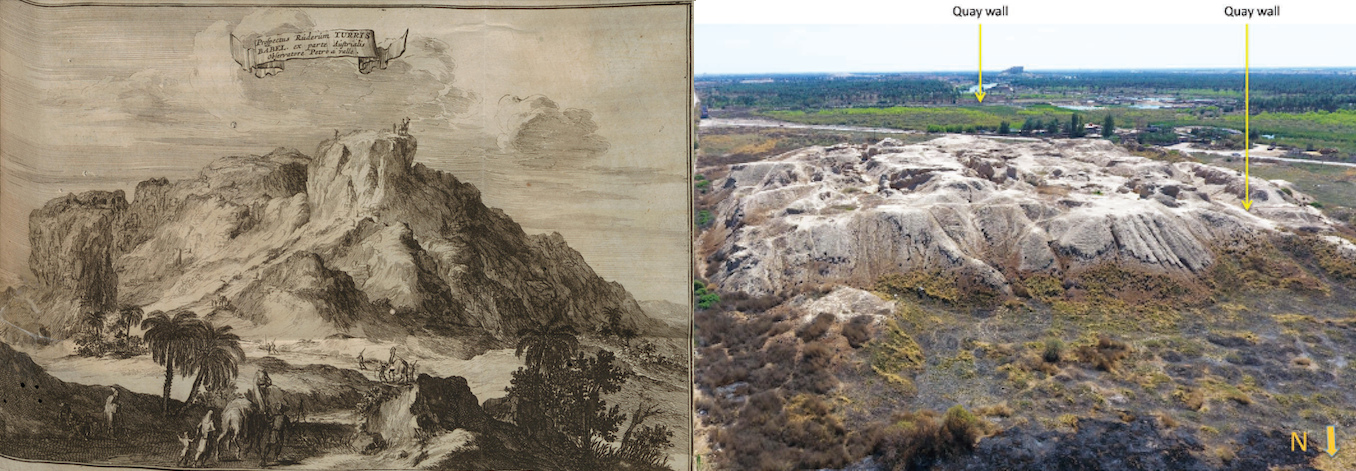

The ruins of the "Tower of Babel," the mound of Tell Babil, according to Pietro della Valle (left); and photograph of the remains of the "Summer Palace" in March 2017 (right). Image created by Jamie Novotny from public domain image on Wikimedia Commons; and O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 135 fig. 3.43.

Archaeological Remains

Thanks to the remarkable high elevation of Tell Babil in contrast to its surroundings, which is largely due to the massive brick terrace built by Nebuchadnezzar II, the site of the Summer Palace attracted the attention of European travelers much earlier than the main part of Babylon. The most famous early exploration was conducted in 1616 by Pietro della Valle, who, because the area was still referred to as Babil, correctly identified the location as Babylon. However, this aristocrat from Rome wrongly believed that the high mound of ruins was the biblical Tower of Babel, whose creation described in Genesis 11:1–9 was meant to explain why the world's population spoke many different languages. della Valle not only had two illustrations of his visit made, but he also took bricks of the palace's founder Nebuchadnezzar written in a then-still-undeciphered cuneiform script.

In 1914–15, Robert Koldewey and his team carried out excavations at Tell Babil and correctly identified the ruins buried within it as a palace built by Nebuchadnezzar; the identification was made from numerous fragments of limestone paving stones that bore an Akkadian inscription mentioning the "palace of Nebuchadnezzar (II)." Some further excavations of the building were conducted by Iraqi archaeologists around 1980. Because brick miners removed baked bricks from Tell Babil for several years after their operations in other parts of Babylon had stopped, parts of the Neo-Babylonian palace were destroyed shortly before Koldewey's started unearthing it. On account of this, as well as further destruction that occurred when a north-south road was constructed directly east of it in the 1920s (and widened in 1981), many uncertainties about its once-grand structure still remain, including its original dimensions.

The palace covered an estimated area of 173×153 m (26,000 m2). Like the North Palace, which was also constructed anew by Nebuchadnezzar, the royal residence had two large central courtyards, with the building's most important rooms constructed to the south of them; the eastern courtyard was larger than the western one (1,600 m2 compared to 1,200 m2). The recessed vertical open channels discovered in the south wall of the east principal room (as well as the room behind the west principal rooms) were thought to have been ventilation shafts for cooling and, thus, suggested that this building was a "Summer Palace" (German Sommerpalast). Approximately seventy rooms have been excavated. The walls were constructed of baked brick and a lime-gypsum mortar; the bricks bore inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar. Some of the floors, the courtyards in particular, were paved with (inscribed) limestone flagstones (60×60 cm); it has been estimated that ca. 6,430 were used to pave the central courtyards.

Plans of the North Palace (left), Summer Palace (middle), South Palace (right). Image created by Jamie Novotny from E. Heinrich, Die Paläste im Alten Mesopotamien, figs. 122, 135, and 138.

According to an Akkadian inscription, Nebuchadnezzar constructed this new palace on top of an artificially-created, 60-cubit (= 30 m) high plot of land, which seems to more or less match the archaeological evidence and explain why Tell Babil rose high above the surrounding plain, even two and a half millennia later. Moreover, that same text states that the building was constructed as "a replica of the palace inside Ka-dingirra" (Akkadian meher ēkal ka-dingirra). The plan of the Summer Palace, as far as it has been excavated, is similar to the western half of the "South Palace," which was in the Ka-dingirra district of East Babylon, as well as to the known ground plan of the "North Palace," which was also build anew by Nebuchadnezzar II and which was built immediately north of the Ka-dingirra district.

From the archaeological record, it is clear that this Neo-Babylonian royal residence remained in use long after the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This is evident from changes made to the building's architecture during the Achaemenid and Seleucid Periods. As is clear from graves cut into the wall(s) of the eastern courtyard, the so-called Summer Palace was no longer used during the Parthian Period. In late Partian Period or in the Sassanian Period, a 180×180 m fortress was built atop its decaying ruins.

Further Reading

- Bergamini, G. 1973. "Parthian Fortifications in Mesopotamia," Mesopotamia 22, pp. 195-214.

- Gasche, H. 2010. "Le palais perses achéménides de Babylone," in J. Perrot (ed.), Le palais de Darius à Suse: Une residence royale sur la route de Persépolis à Babylone, Paris, pp. 446–463.

- Heinrich, E. 1984. Die Paläste im Alten Mesopotamien, Berlin, pp. 223–226.

- Invernizzi, A. 2000. "Discovering Babylon with Pietro della Valle," in P. Matthiae (ed.), Proceedings of the First International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Rome, pp. 643–649.

- Invernizzi, A. (ed.) 2001, Pietro della Valle. In viaggio per l'Oriente. Le mummie, Babilonia, Persepoli, pp. 29–56.

- Koldewey, R. 1932, Die Königsburgen von Babylon 2: Die Hauptburg und der Sommerpalast Nebukadnezars im Hügel Babil (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 55), Leipzig, pp. 41–62.

- Koldewey, R. 1990. Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition (edited by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 19–25.

- Pedersén, O. 2020. Babylon: The Great City, Münster, pp. 104–106.

- Wetzel, F., Schmidt E., and Mallwitz, A. 1957. Das Babylon der Spätzeit, Berlin, pp. 24–25.

Banner image: satellite image of Tell Babil; digital reconstruction of the so-called Summer Palace; and excavation plan of the ruins of the Neo-Babylonian palace at Tell Babil. Adapted by Jamie Novotny from Koldewey, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition, fig. 3; and O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, p. 136 fig. 3.44.

Giulia Lentini & Jamie Novotny

Giulia Lentini & Jamie Novotny, 'Summer Palace (royal palace in Babylon)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/Palaces/SummerPalace/]