South Palace (royal palace in Babylon)

The remains of the so-called "South Palace," which was the largest of the three royal residences of ancient Babylon, were buried beneath the Qasr ("palace"), a mound of ruins whose name local tradition had maintained as the location of Babylon's palace for over two millennia. This once-grand royal building extended over an area of 45,000 m² and was enclosed by an imposing fortification wall. Located in the northwest corner of East Babylon, the South Palace was bounded on the north by the inner city wall Imgur-Enlil, on the south by the canal Lībil-hegalla, on the west by the bank of the Euphrates river, and on the east by the Processional Way of Babylon's patron god Marduk, Ay-ibūr-šabû. This extensive structure was not only the living quarters of the royal family, but it was also the principal administrative center and the main reception hall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

Names and Spellings

"South Palace" (German Südburg) is the modern designation of the palace given to it by the German archaeologists who excavated it at the beginning of the twentieth century. Because it was the southernmost of the two royal residences in the inner city of East Babylon, it was designated as the "South Palace"; Nebuchadnezzar II's new palace was called the "North Palace."

In antiquity, Babylonian kings simply referred to the building as ēkallu, the Akkadian word for "palace." Sometimes, texts specified its location as being "inside the city" (ša qereb āli) or "in the district of Kadingirra" (ina erṣet Kadingirra). Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC), the most famous of the Neo-Babylonian rulers and the first king to construct the building as his main residence, regularly referred to this palace as "the house (which was) an object of wonder for the people" (bīt tabrāt nišim), "the residence of my royal majesty" (mūšab šarrūtīya), "the bond of the land" (markas māti), "a holy private room" (kummu ellu), "the abode of my royal majesty" (atman šarrūtīya), "the seat of joyous celebrations" (šubat rīšāti u ḫidâtim), and "the place where important people submit" (ašar kadrūtim uktannašū). In the Achaemenid Period, administrative documents from the reign of Darius I (r. 522–486 BC) referred to the building as the "large palace" (ēkallu rabû). Babylonian Chronicles and astronomical diaries dated to the Seleucid (331–141 BC) and Parthian (141 BC–224 AD) Periods referred to this structure as "the king's palace" (ēkal šarri), "the king's palace that is in Babylon" (ēkal šarri ša ina Bābili), "the palace of Babylon" (ēkal Bābili), and "the palace" (ēkallu).

- Written Forms: É.GAL; É.GAL.É.GAL; É.GAL-ia; e-ka-al-lam

Known Builders

- Neo-Babylonian (ca. 625–539 BC)

- Nabopolassar (r. 625–605 BC)

- Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BC)

- Neriglissar (r. 559–556 BC)

- Nabonidus (r. 555–539 BC)

- Achaemenid (547–331 BC)

- Cyrus II (r. 539–530 BC)

- Cambyses (r. 530–522 BC)

- Darius I (r. 522–486 BC)

- Artaxerxes II (r. 404–358 BC)

Building History

A palace at Babylon is attested in the Old Babylonian Period (ca. 1900–1600 BC), during the reigns of Hammu-rāpi (r. 1792–1750 BC), Samsu-iluna (r. 1749–1712 BC), and Ammī-ditāna (r. 1683–1647 BC), when Babylon was the most dominant and influential political power in southern Mesopotamia. Two year names — Samsu-iluna Year 34 (1721 BC) and Ammī-ditāna Year 20 (1664 BC) —mention Babylon's royal residence. Due to the high groundwater level at Babylon, which makes it impossible to explore the Old Babylonian strata, it is unknown if this Old Babylonian building was located in the same place as the so-called "South Palace" built by the kings of the Neo-Babylonian Period (ca. 625–539 BC) a thousand years later. Already in the sixth century BC, the high waters levels at Babylon were a problem, as recorded in several inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II, which state that the foundations of the palace of his father Nabopolassar had become weak due to water damage; that building is reported to have been constructed from unbaked/sun-dried bricks (Akkadian libittu). Before rebuilding himself a new royal residence, Nebuchadnezzar had the building site significantly raised with bitumen (Akkadian kupru) and baked bricks (Akkadian agurru). The elevation change of the palace's site was also necessary because Nebuchadnezzar had significantly raised the level of the Processional Way Ay-ibūr-šabû, which ran along the building's eastern façade and, thereby, made access to the palace problematic since its (principal) entrances were below street level.

After tearing down and removing the remains of Nabopolassar's palace and raising the height of the site above the level of the groundwater and in line with the height of the directly-adjacent Ay-ibūr-šabû, Nebuchadnezzar built himself a new royal residence. One inscription describes the construction as follows:

Client kings from all over the empire, especially from the Levant, and provincial governors supplied labor and materials for the palace's construction. Despite Nebuchadnezzar's claims that he had built his residence as "an object of wonder for the people" (Akkadian tabrāt nišim), his inscriptions, as is typical for Neo-Babylonian inscriptions, provide few details about this largescale building project.

The palace remained in use throughout the rest of the Neo-Babylonian Period. Nebuchadnezzar's son-in-law and second successor Neriglissar had to rebuild the western part of the palace after part of the building collapsed onto the bank of the Euphrates River (Šaṭṭ al-Ḥillah, a modern branch of the river). Nabonidus, the last native king of Babylon, according to archaeological evidence, repaved the floors of the three courtyards in the eastern part of the building.

After the Persian king Cyrus II defeated Nabonidus in 539 BC, thus bringing native rule of Babylonia to an end, Babylon retained its role as an important administrative center. When Achaemenid rulers visited the city, they stayed in the South Palace. Although restorations and repairs from this time are not presently attested in extant textual sources, they are evident from the archeological record. During the reigns of Cyrus II and his son Cambyses, as well as under Darius I, building activities were conducted in the so-called "Main Courtyard," with the addition of a square tower (in the north-western corner) and a basin (in the middle). Moreover, following architectural models from Susa, an important religious and administrative center in the heart of the Persian Empire, these kings rebuilt the two courtyards of the western half of the building. Artaxerxes II, Darius I's sixth successor, constructed a new pavilion outside the palace's western wall. This structure, which was modelled on buildings in the Persian capitals of Susa and Persepolis, was called the "Perserbau" by the archaeologists who excavated it.

The South Palace remained in use to some extent during the Seleucid Period (331–141 BC). It is possible that this was the very place where Alexander the Great died in 323 BC, according to Classical sources. Alexander's successors, the Seleucid rulers who held authority over Mesopotamia, like the Achaemenid kings, used this palace as their residence when they visited Babylon, even after Seleucia on the Tigris became the new administrative capital.

During the Parthian Period (141 BC–224 AD), some wall structures were added in the three courtyards of the eastern half of the building, when the palace was still in use. At a later point in time, however, the palace lost its function and was used for burials.

Archaeological Remains

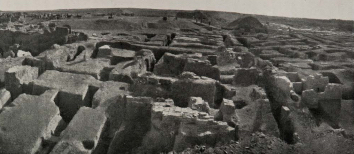

German excavations of the South Palace, looking from north. Adapted from Koldewey, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition, fig. 54.

The substantive remains of the South Palace were unearthed during the German excavations (led by Robert Koldewey) in 1900–1, 1903–7, and 1912–13. Around 1980, Iraqi archaeologists re-excavated this massive royal residence and reconstructed the building's walls on their still–standing lower wall sections and foundations. Because the level of the modern groundwater is high, nearly all of the archaeological evidence for this palatial structure comes from the Neo-Babylonian and later periods, with the exception of limited nearby evidence from the late Neo-Assyrian Period (721–612 BC).

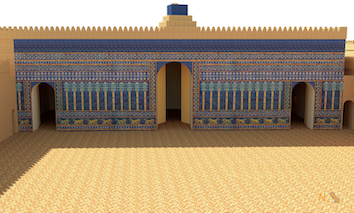

Reconstruction of the Middle and Main Courtyards, looking southwest. Adapted from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, fig. 3.15.

The South Palace, which was constructed anew in its entirety by Nebuchadnezzar II, comprises a total area of 45,000 m² (or 4.5 ha). The outer fortification walls measure 300 m long east to west, 190 m long north to south on the eastern side, and 126 m long north to south on the western side. This impressive building had approximately 600 rooms arranged around 5 large and 50 small courtyards. From east to west, the principal courtyards were referred to by their excavators as the "East Courtyard," the "Middle Courtyard," the "Main Courtyard," the "West Courtyard," and the "Annex Courtyard." The most important one, the "Main Courtyard," was in the middle of the palace and it provided direct access to the throne room (the largest room in the building). The courtyard entranceways were flanked by towers that were decorated with glazed bricks and lion reliefs. The south wall of the "Main Courtyard," which had three doors granting access to the throne room, was completely decorated with a majestic mural that depicted striding lions, columns with capitals, and floral friezes on a dark blue background; part of this decoration is now reconstructed in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin. The north wall of the throne room was completely black. The interior walls of some rooms were decorated with a white lime-gypsum plaster. In the northeast corner of the palace, there were underground basements beneath vaulted chambers. Moreover, there were staircases that gave access to upper floors and/or the roof.

Reconstruction of the Main Courtyard and the façade of the throne room with glazed brick decoration, looking south. Adapted from O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, fig. 3.17.

The palace, in its final Neo-Babylonian form, was constructed above the remains of an older building phase (probably also dating to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar rather than that of his father Nabopolassar) that is characterized by the use of small, uninscribed bricks. When the next, higher level of the palace was built, Nebuchadnezzar used the older walls as foundations. The remains of this older phase of the palace's construction were generally well preserved.

From the archaeological record, it is clear that the South Palace continued to be used long after the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC. For the Achaemenid Period, this is clear from the western part of the building, where the so-called "Perserbau" was built by Artaxerxes II. For the Seleucid Period, however, remains in the South Palace were limited to small finds, such as sealed clay bulla, black pottery, and terracottas. In the Parthian Period, structures made of brick fragments were added to the older walls in the three courtyards of the eastern half of the building. Only at the end of this period, when the palace seems to have lost its original function, its "Main Courtyard" was used for burials, as attested by the many graves found there.

Further Reading

- Gasche, H. 2010. "Le palais perses achéménides de Babylone," in J. Perrot (ed.), Le palais de Darius à Suse. Une residence royale sur la route de Persépolis à Babylone, Paris, pp. 446–463.

- Haerinck, E. 1990. "Babylon unter der Herrschaft der Achaemeniden," in R Koldewey, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition (edited by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 372–384.

- Hauser, S.R. 1999. "Babylon in arsakidischer Zeit," in J. Renger (ed.), Babylon: Focus mesopotamischer Geschichte, Wiege früher Gelehrsamkeit, Mythos in der Moderne, Saarbrücken, pp. 207–239.

- Heinrich, E. 1984. Die Paläste im Alten Mesopotamien, Berlin, pp. 203–221.

- Koldewey, R. 1931. Die Königsburgen von Babylon 1: Die Südburg (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 54), Leipzig.

- Koldewey, R. 1990. Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition (edited by B. Hrouda), Munich, pp. 79–139.

- Pedersén, O. 2021. Babylon: The Great City, Münster, pp. 71–87.

- Vallat, F. 1989. "Le palais d'Artaxerxes II à Babylone," Northern Akkad Project Reports 2, pp. 3–6.

- Wetzel, F., Schmidt E., and Mallwitz, A. 1957. Das Babylon der Spätzeit, Berlin, pp. 25–27.

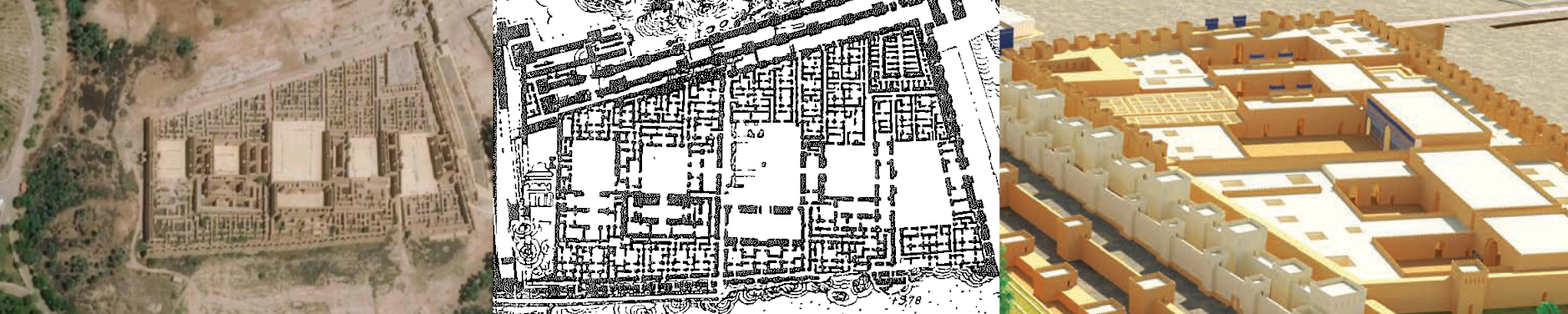

Banner image: satellite image of the reconstructed South Palace (left); plan of the ruins of the South Palace (center); and modern reconstruction of the South Palace (right). Adapted from Koldewey, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, fifth edition, fig. 256; and O. Pedersén, Babylon: The Great City, figs. 3.5 and 3.42.

Giulia Lentini & Jamie Novotny

Giulia Lentini & Jamie Novotny, 'South Palace (royal palace in Babylon)', Babylonian Temples and Monumental Architecture online (BTMAo), The BTMAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, [http://oracc.org/btmao/Babylon/Palaces/SouthPalace/]