Project

The project Reading the Library of Ashurbanipal: A multi-sectional Analysis of Assyriology's Foundational Corpus is a collaborative project based at the British Museum and Ludwig Maximilian University Munich. It is funded by the AHRC and DFG (AH/T012773/1) and runs from 2020-2023.

Ashurbanipal's Library has been a central resource for assyriology ever since it was first discovered. Over the last 170 years, scholars from around the world have studied it intensely. So we know a lot about some of the texts in it, like the famous Gilgamesh Epic. But despite all this, we don't know much about the library as a collection. Modern attempts to understand it have been frustrated by its overwhelming size and complexity. The few attempts that have been made to explain the Library are based on surprisingly limited evidence. They can present almost completely opposite interpretations.

There are no contemporary accounts of the Library, and no descriptions in official inscriptions. But scribal notes added to the end of the tablets (known as "colophons") give us direct evidence about how and why they were produced. They have never been studied from this perspective. The simple presence of a library "colophon" also confirms that the tablet in question definitely came from Ashurbanipal's collection. How many tablets were there? Estimates range from as few as 2,000 to more than 10,000. It is not always clear which tablets actually belonged to the Library, and which belonged elsewhere. Some tablets excavated at Nineveh had been dedicated to the god of writing or had belonged to private collections. How were they related to Assurbanipal's collection? How did the scribes decide which of the dozens of standardised library colophons belonged on which tablet? Reading the Library of Ashurbanipal will for the first time identify and analyse all fragments bearing colophons.

Reading the Library of Ashurbanipal will look at the corpus of literary tablets in the Library. How cohesive is that corpus? Where did the tablets come from? We will correlate the tablets themselves with information gained from lists recording the arrival of tablets following the Assyrian capture of Babylon in 648 BC. These detail the scribe who the volumes were taken from, the title of the composition, and the format and number of volumes. This must have been a significant acquisition. Until now, it has not been possible to identify surviving tablets among those listed in the inventories.

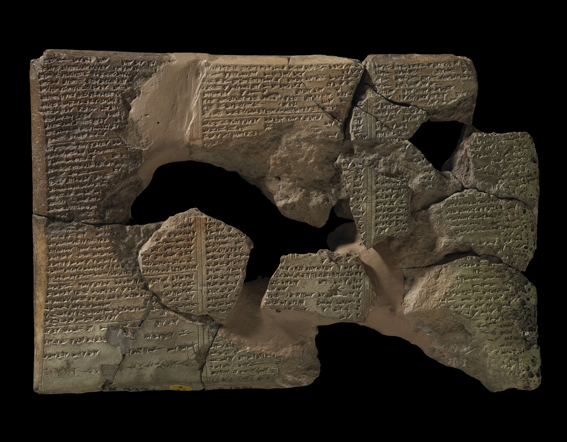

The tablet containing the Babylonian Flood Story, as reconstructed from fragments by George Smith in 1872. K 2252+K 2602+K 3321+K 4486+Sm 1881 [https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_K-2252]. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 [https://www.britishmuseum.org/terms-use/copyright-and-permissions]

It is often said that Ashurbanipal's Library contained a copy of every significant scholarly text known at that time. Typically, most of the sources for such a text, and also the most complete individual sources, derive from this library at Nineveh. There are texts from Nineveh not known from elsewhere, yet rarely texts known only from elsewhere. Following the discovery of tablets at Sultantepe in 1950s, a new text called "The Poor Man of Nippur" was found. Shortly afterwards, a duplicate was identified among the Nineveh texts.

How comprehensive was Ashurbanipal's collection? The lack of editions of many omen and magical texts hinders any thorough study of that question. But the corpus of literary texts is much better studied. The 1,000 or so tablets and fragments from Nineveh represent a meaningful and manageable corpus. They allow us to gain a cross-section through the collection.

How does the collection known to us relate to the collection assembled in antiquity? Once all the literary fragments are identified, and any joins are made, we will have a corpus of tablets reconstructed to the fullest extent possible. How complete will those tablets be? It has always been said that once all the fragments are re-joined, we will have more or less complete tablets. All the pieces should be in the British Museum collection somewhere, waiting to be found. That assumption is now difficult to sustain. The tablets containing the Gilgamesh Epic, for example, can be as much as 80% or more complete, but many are less than 50% complete. It is clear that what was found in the 19th century was not the remains of collapsed bookshelves.

The project team

Dr Jon Taylor: PI, British Museum

Prof. Enrique Jiménez: PI, LMU Munich

Babette Schnitzlein: Project Curator, British Museum

Sophie Cohen: PhD student, LMU Munich

Mays Al-Rawi: MA student, LMU Munich

Ekaterine Gogokhia: MA student, LMU Munich

We would like to thank the following colleagues for their help and contributions:

- Eckart Frahm

- Ulla Koch

- Christopher Walker

- Maeve Weber

- the electronic Babylonian Literature project, University of Munich

- Jamie Novotny

Jonathan Taylor

Jonathan Taylor, 'Project', Reading the Library of Ashurbanipal, Reading the Library of Ashurbanipal project, Department of the Middle East, The British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG and Institut fuer Assyriologie und Hethitologie, Ludwig Maximilian University, Geschwister Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 Munich, 2022 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/RLAsb/Project/]